Indigenous Visions: Immersive 360 Storytelling in the Amazon

360° Video footage of a waterfall near the community of Dicaro in Yasuní National Park and Biosphere Reserve in Eastern Ecuador. Explore by clicking and dragging your mouse around the scene.

Produced by: Jorge Castillo Castro

We are all here on this planet today thanks to the power of story. Through stories, our ancestors transferred indigenous wisdom from one generation to the next, giving us the necessary insight into how to coexist with the environment around us and use our natural resources to survive.

Until, that is, society became so globalized and digitized that we began losing track of that indigenous ancestral wisdom. A rift began forming between those who have access to digital technology and who know how to use it and those who do not. We now call this rift the digital divide.

Yet, what if digital technology could actually be used to conserve ancestral wisdom in areas that have traditionally lacked access to or understanding of such technology? And what if storytelling can serve as the familiar link between the two? That is what this research set out to explore.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

In the summer of 2014, environmental communicators Megan Westervelt and Jorge Castillo Castro spent three months collaborating with indigenous photographers in several Waorani (pronunciation guide: WOW-RA-KNEE) in Yasuní National Park, Ecuador, to create a documentary about Wao culture. They simultaneously offered photography workshops to community members interested in learning the skills of visual storytelling with DSLR cameras. During that time, Megan unknowingly became an anthropologist, as well. She instinctively began taking mental and photographic notes of the behaviors, language, and interactions of the community members around her.

Megan made several intriguing observations that have lived in her mental notebook ever since. It is thanks to these observations and her keen interest in continuing to work with these communities, where she has built relationships of trust and mutual respect. That is where our story begins today…

360° Drone footage above the canopy of Yasuní National Park, Eastern Ecuador. Explore by clicking and dragging your mouse around the scene.

Produced by: Jorge Castillo Castro

The Backstory

Google Earth animated map of the country of Ecuador

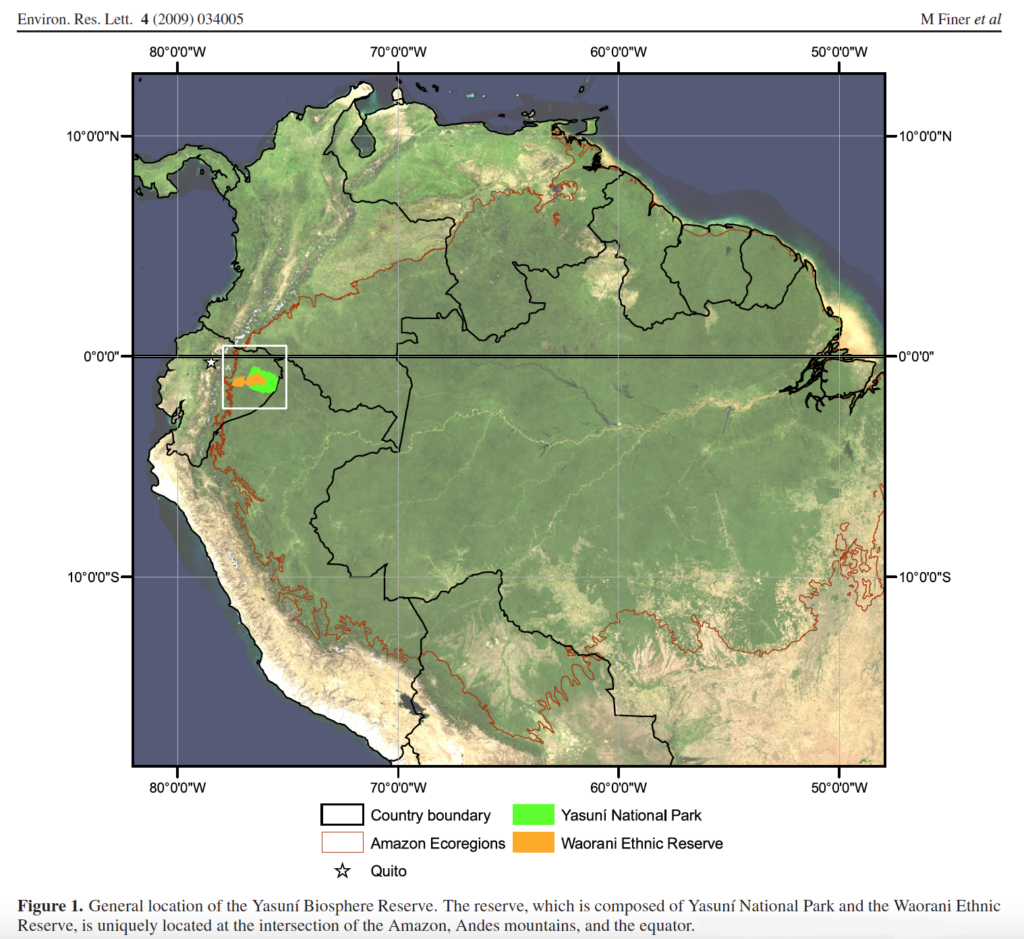

In recent years, there has been a notable increase in the amount of attention paid to conservation efforts around the globe because of climate change and the impact of natural disasters on society. Within this context, Bass et al. (2010) made a convincing and well-supported argument for the need to focus on conservation efforts within Yasuní National Park in Amazonian Ecuador. According to the first comprehensive synthesis of biodiversity data for Yasuní, which Bass et al. (2010) conducted, Yasuní has “outstanding global conservation significance” because of its extraordinary, unparalleled biodiversity and its potential to continue sustaining said biodiversity for the long term (p. 1). The research concludes that Yasuní is a valuable biological treasure due to its unique characteristics, including its large size and wilderness, intact large-vertebrate populations, internationally protected status in a region otherwise void of protected areas, and potential for maintaining wet, tropical rainforest conditions despite projected climate change impact on the region.

Finer, M., Vijay, V., Jenkins, C. N., Ponce, F., & Kahn, T. R. (2009). Ecuador’s Yasuní Biosphere Reserve: A brief modern history and conservation challenges. Environmental Research Letters, 4(3), 1–15. https://doi-org.proxy.library.ohio.edu/10.1088/1748-9326/4/3/034005

Bass et al. (2010) also offered an explanation for why the conservation of Yasuní is so necessary at this time; Ecuador’s second largest untapped oil field lies directly beneath the northeastern sector of the Park, and as the country’s primary export, oil is in high demand (Finer et al, 2009). Previous oil exploration and exploitation in Yasuní have already led to the construction of four oil access roads, which have “facilitated colonization, deforestation, fragmentation, and overhunting of large fauna” (Bass et al., 2010, p. 2). However, according to Finer et al. (2009), oil extraction is not the only growing threat confronting conservation efforts in Yasuní Biosphere Reserve (which includes both the National Park and the Waorani Ethnic Reserve); illegal logging has also been growing and resulting in deadly encounters between loggers and uncontacted groups. In their article, Finer et al. (2009) revealed the current conservation challenges in Yasuní Biosphere Reserve in terms of both the biodiversity and the indigenous groups who call Yasuní home, including the relatively recently contacted group known as the Waorani (or Huaorani) and two uncontacted groups.

Map of Yasuní National Park indicating the location of the Waorani community of Dicaro, our principal field research site.

Created by: Jorge Castillo Castro

Bass et al. (2010) proposed five policy recommendations for conservation efforts in Yasuní in light of their scientific findings; however, none of the recommendations involved working with local, indigenous stakeholders in collaboration towards conservation. In contrast, Finer et al. (2009) concluded that, despite the Waorani people’s continued search to “find their place in the modern world,” they are “important actors in an ongoing struggle for cultural survival, territorial integrity, and the protection of their uncontacted relatives, along with new efforts to promote sustainable development” (p. 13).

Jungle canopy in the afternoon near Dicaro. Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Storytelling has been a fundamental element of human society since our origin, with its earliest roots tracing back to indigenous cultures around the globe. In their publication on education through storytelling, Lawrence and Paige (2016) explained that storytelling has primarily served two purposes: “to entertain and to teach people how to become better human beings” (p. 63). Within the latter objective, many indigenous peoples have sought to maintain their connection with the Earth through storytelling: “stories conveyed a powerful message about treating the earth like a grand home” (Lawrence and Paige, 2016, p. 64).

This article serves to illuminate the many additional purposes for and uses of storytelling that have developed over time. First, because many history books do not include indigenous stories, “oral [storytelling] is a way to keep these stories alive while challenging dominant discourse” (Lawrence & Paige, 2016, p. 65). Secondly, stories also connect us so that we may find meaning in our own individual experiences and those that we share with others. Additionally, since many stories involve a problem, solution, and moral, they serve to teach about particular themes and lessons, “allowing the listener or reader to draw his or her own conclusions” (Lawrence & Paige, 2016, p. 66). Finally, stories help us explore alternative possibilities and realities, such as lived experiences by minority or underrepresented groups.

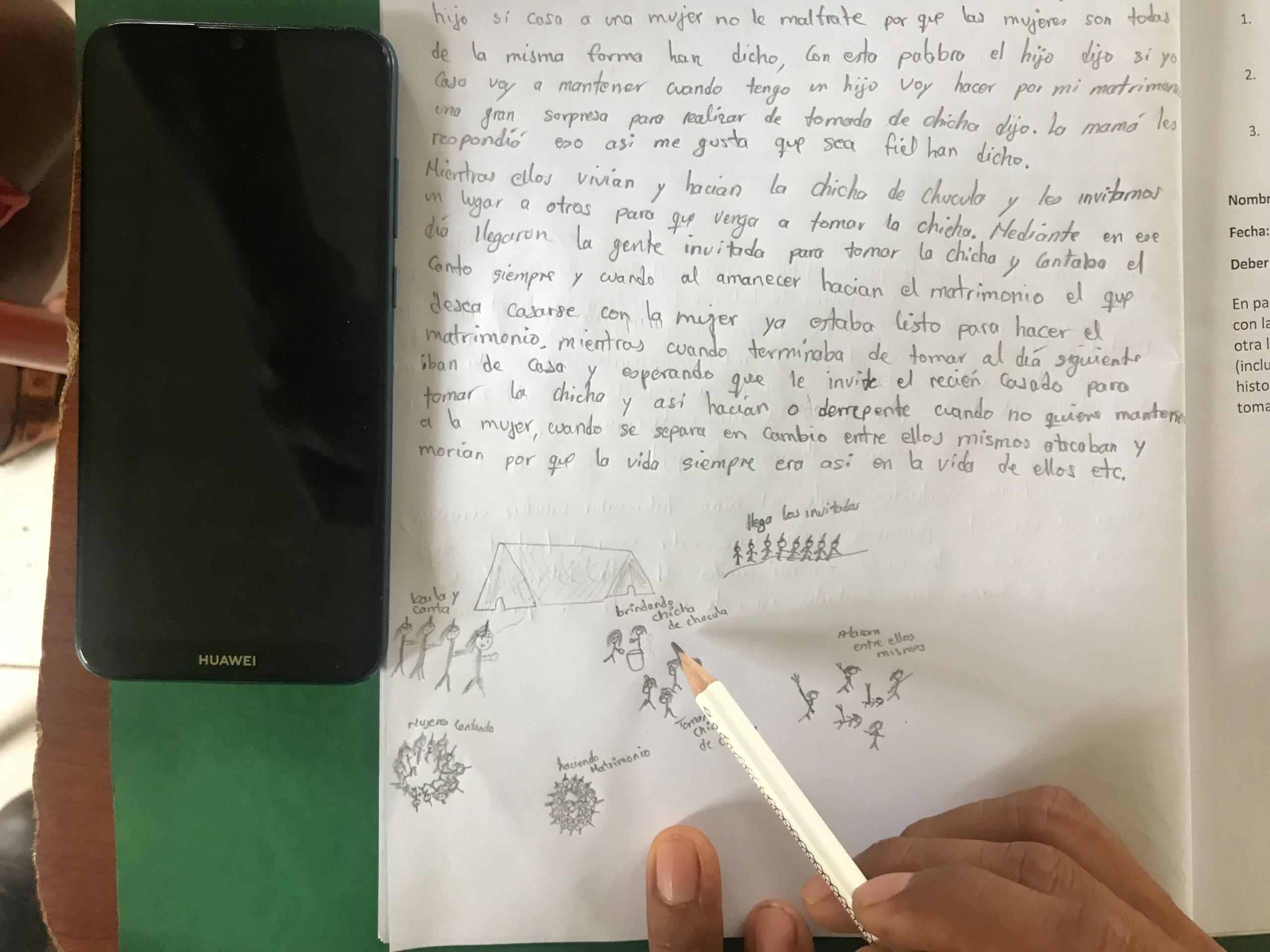

Awa Nampahue explains the story he drew during the workshop facilitated by Jorge Castillo Castro and Diana Troya, designed by Megan Westervelt.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

In her article, Brown (2013) offered a well-supported argument for the necessity of storytelling to be a part of ecological management, synonymous with conservation. Brown included over a dozen examples that showed how indigenous stories have been and should continue to be used as “tools to guide humans through complex interactions with ecosystems and to remember our shared fate with the land” (abstract). Most importantly for this current study, Brown established an evidenced link between storytelling and culturally based resource management through the lens of empathy. She concluded that:

Empathy has been traded for efficiency in industrial societies, especially empathy for non- human entities. I believe empathy for places, plant and animals is a necessary social adaptation that helps groups of people receive the necessary feedback from their actions.

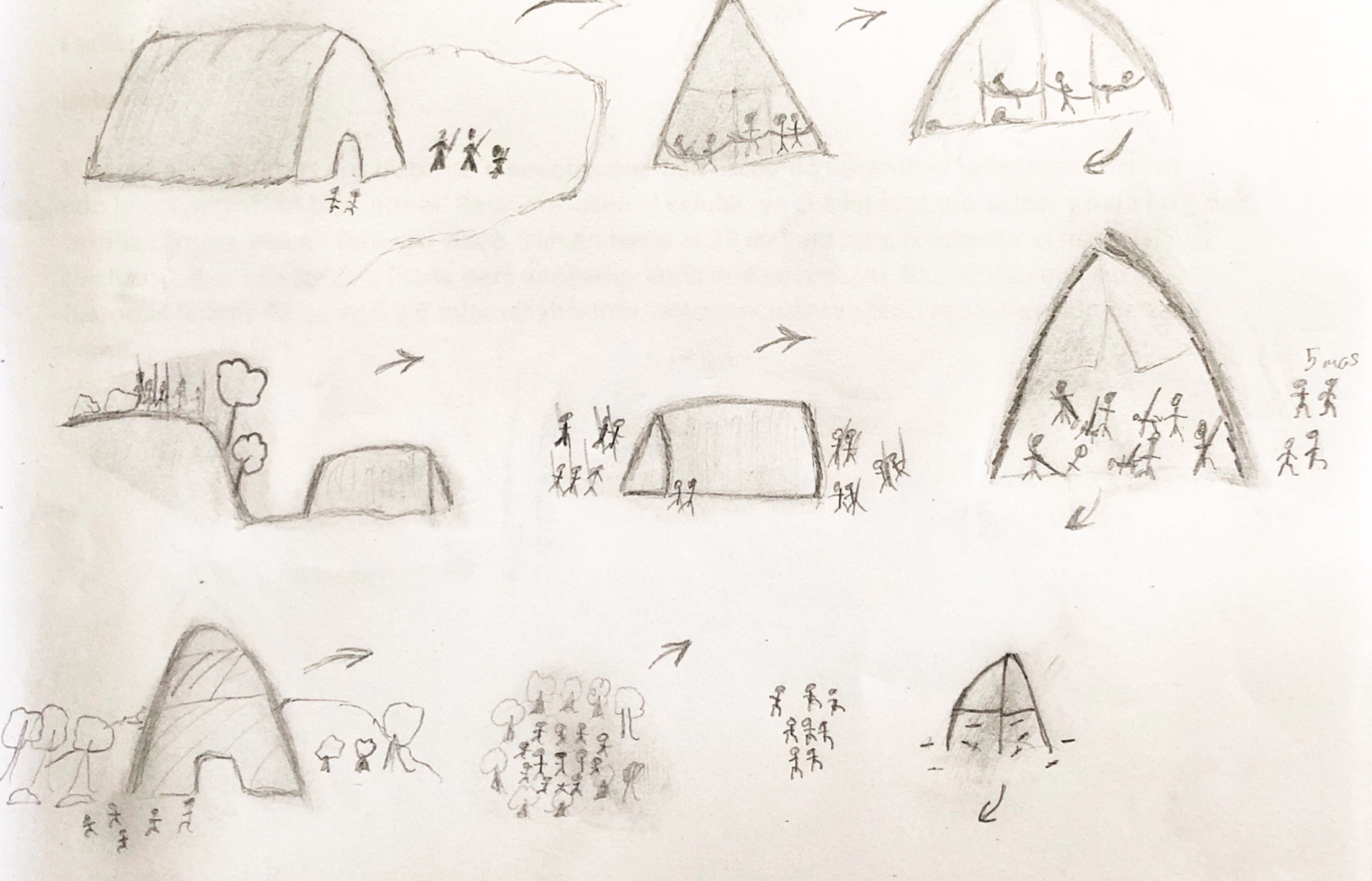

An example of a participant’s hand-drawn story created during the workshop facilitated by Jorge and Diana, designed by Megan.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

The connection between indigenous culture and biodiversity has also been well established in published literature. In their seminal article, Gavin et al. (2015) presented the concept of biocultural approaches to conservation as follows: “the conservation actions made in the service of sustaining the biophysical and sociocultural components of dynamic, interacting, and interdependent social-ecological systems” (p. 140). The article includes eight principles required for successful biocultural conservation efforts, of which one speaks to the role of indigenous storytelling in conservation specifically. Gavin et al. emphasized the importance of considering the social-political context for conservation planning to ensure success (2015).

From a global perspective, another article reviewed the potential for intergovernmental agencies to develop policy that combines both biological and cultural diversity agendas, adopting a biocultural approach to national and international agenda-setting (Fernández & Cabeza, 2018). As the authors explained, “because indigenous stories are full of resonance, memory, and wisdom,” they can play a key role in future biocultural conservation (p. 1). To provide an explanation of the linkages between indigenous storytelling and conservation practice, the article offers a very insightful conceptual map outlining the elements involved in biocultural conservation, including intergenerational communication, indigenous worldviews, dialogue, local participation, sense of place, knowledge co-production, intercultural discussions, emotion-action, and, of course, indigenous storytelling. This diagram also illustrates the relationships between the various elements. In addition, Fernández and Cabeza (2018) published an overview of numerous examples of conservation initiatives that have utilized indigenous storytelling and the challenges and limitations involved in this biocultural approach. A most important discussion of ethics is included at the close of their article, as well.

A drone photo shows where a swath of tropical jungle has been cut down and burned to create space for a cacao plantation near the Waorani community of Dicaro.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

The means by which we might weave together the educational potential of storytelling, the biocultural approach to conservation, and the apparent need for a concentrated focus on conservation in Yasuní may lie within the Waorani culture itself. Like many indigenous groups, the Waorani still pass on traditional knowledge from one generation to the next through oral storytelling (Singh et al., 2010; Kane, 1996). Singh et al. (2010) defined traditional knowledge as “a body of knowledge accrued within a group of people across generations of close contact with nature,” which transforms over time in reaction to changes in the local environment (p. 511). A synthesis of community activities designed to promote both the learning about and conservation of traditional knowledge and related biocultural resources within tribal groups in northeast India provides an example of how participation of community members with traditional knowledge can “enhance the promotion of traditional practices, learning of knowledge and conservation of related resources”—in essence, using a biocultural approach to conservation (Singh et al., 2010, p. 511). In their perspective paper, McSweeney and Pearson (2009) alluded to the fact that not only a biocultural but also a Waorani-inclusive approach was necessary in Yasuní to ensure successful and long-lasting conservation initiatives. To echo their argument, many studies have shown that the most important actors for biodiversity conservation are the local, long-term residents of the area (McSweeney & Pearson, 2009). Thus, it is vital to expand our understanding of the role that indigenous Waorani storytellers can play in forwarding biocultural conservation of Yasuní.

The use of digital storytelling for cultural preservation (Reitsma et al., 2013; Iseke & Moore, 2011; Gomez et al., 2018) and for community empowerment (Li, 2009; Torrez et al., 2017; Lefkowich et al., 2019) has been well established in prior research and published literature. However, there is a notable gap in the use of digital storytelling for environmental, or even biocultural, conservation purposes. This proposed study aims to build on the foundations of prior research to expand our collective understanding of what might be possible when combining indigenous cultural wisdom (through traditional-knowledge stories), digital storytelling, and a specific focus on the environment to assess how digital storytelling might play an active role in community-led conservation efforts.

The hands of a semi-domesticated spider monkey emerge from the window of a home in the Waorani community of Dicaro.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

360° Video footage of Megan and Jorge conducting a concluding interview with participant and filmmaker Jose Omehuai. Explore by clicking and dragging your mouse around the scene.

Produced by: Jorge Castillo Castro

The Critical Questions

In the Waorani community of Dicaro in northern Yasuní National Park, how does traditional storytelling impact an individual’s understanding of natural resource use/depletion and/or biocultural conservation?

What themes related to land, environment, and/or natural resources can be found within traditional stories passed from one generation to the next in the community?

What is the potential for digital storytelling to impact an individual’s understanding of natural resource use/depletion and/or biocultural conservation?

How does the process of creating and sharing digital stories involving the environment impact an individual’s attitude about and/or behavior towards natural resource use/depletion and/or biocultural conservation?

How does the digital divide (access to and/or knowledge about digital devices) impact the potential role of digital storytelling in understanding, communicating, and/or addressing environmental challenges in the community?

360° Video footage of Jorge and Diana leading the immersive storytelling portion of the workshop in August 2021 with Ava and Manuel, two of the participants of the research study. Explore by clicking and dragging your mouse around the scene.

Produced by: Jorge Castillo Castro

Methodology and Field Research

Given the multidisciplinary approach of this project, it is vital to understand the contextual and theoretical underpinnings that will guide the research and production processes. This study will operate under the assumptions proposed by Media for Social Change theory (Bolin, 2019; Kent &Taylor, 2021) and the concept of digital divide. Media for Social Change theory focuses on how media can empower communities to affect social change that they envision for themselves. Digital divide refers to the gap between those who can access internet and communication technologies and those who cannot, as well as those who are literate in using such technologies and those who are not (Yu et al., 2016). By following a theory based on problem-solving through media production, this study will benefit from the transparent bias towards empowering communities to think about social change that they envision for themselves. By also considering the digital divide, this study will ensure that the researchers meet participants wherever they are with their understanding of digital devices and communication.

This study incorporated two qualitative research approaches (narrative and ethnographic) in its methodological design that work well with Media for Social Change theory and the challenges presented by the digital divide in terms of access to and knowledge about internet and communication technologies (ICT). Narrative approach is based upon in-depth interviews that allow for the participant to guide much of the process (McCormack, 2004). Ethnographic approach primarily involves participant observation to learn about “particular, local worlds through direct engagement with their peoples and ways of life” (Comaroff, 2005, p.725).

Within the narrative approach, this project relied heavily upon the method of photovoice to provide the tools and training so that indigenous community members can use digital storytelling to better understand, communicate, and/or address environmental challenges. As described by the researchers who coined the term, “photovoice is a process by which people can identify, represent, and enhance their community through a specific photographic technique” (Wang and Burris, 1997, p. 369). The photographic technique in the case of this study was two-fold: photos/videos created using the participants’ own devices (cell phones or tablets) and photos/videos created used immersive 360 cameras. In both cases, the equipment was placed in the hands of the community members who are participating so that they could capture their own stories to share. Within the ethnographic approach, the research assistants working in the field documented their observations of the participants’ interactions with digital technology specifically, focusing on creating an ethnography of technology. This was done to understand the effectiveness of the workshop approach to digital storytelling training. We would debrief by text messages or voice calls almost every evening after the research activities had concluded.

Jorge and Diana review the production process for the 360° video using their cellphones during the pre-field training in Quito, Ecuador.

Photo Credit: Megan Westervelt

Pre-field Training and Participant Selection

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, our research team decided to try the unthinkable: participatory field research while based in a remote community with no running water and unreliable electricity. With the support from a Student Enhancement Award (Ohio University) and personal funds, we planned a month-long field research component that would implement the first of three stages in our research plan. Megan organized and facilitated a week-long pre-field training in the capital city of Quito so that Jorge and Diana would feel comfortable with the purpose of the study and the many steps involved in conducting the fieldwork, as detailed in the IRB (approved just prior to beginning fieldwork). As a team, we planned how we would debrief at the end of each day of field research and discuss Jorge and Diana’s ethnographic fieldnotes.

The first step in the process—arguably the most important—was to select our participants who would be asked to work with us from August through December. While we outlined a list of criteria for participants, we were most interested in collaborating with individuals who (1) most often use digital technology, (2) expressed a connection between storytelling and understanding environmental challenges in their community, and (3) were willing to publish their stories online. After conducting selection interviews, our team briefly analyzed the responses to choose the six potential candidates who most closely aligned with our three main criteria listed above. We cannot overstate our tremendous gratitude for the willingness of these individuals to not only participate in this study, but also to teach us so much on a daily basis. They all continue to inspire us to this day with their stories and ideas.

Diana conducts a selection interview with Karina Boya in her home in community in Dicaro.

Diana conducts a selection interview with Karina Boya in her home in community in Dicaro.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

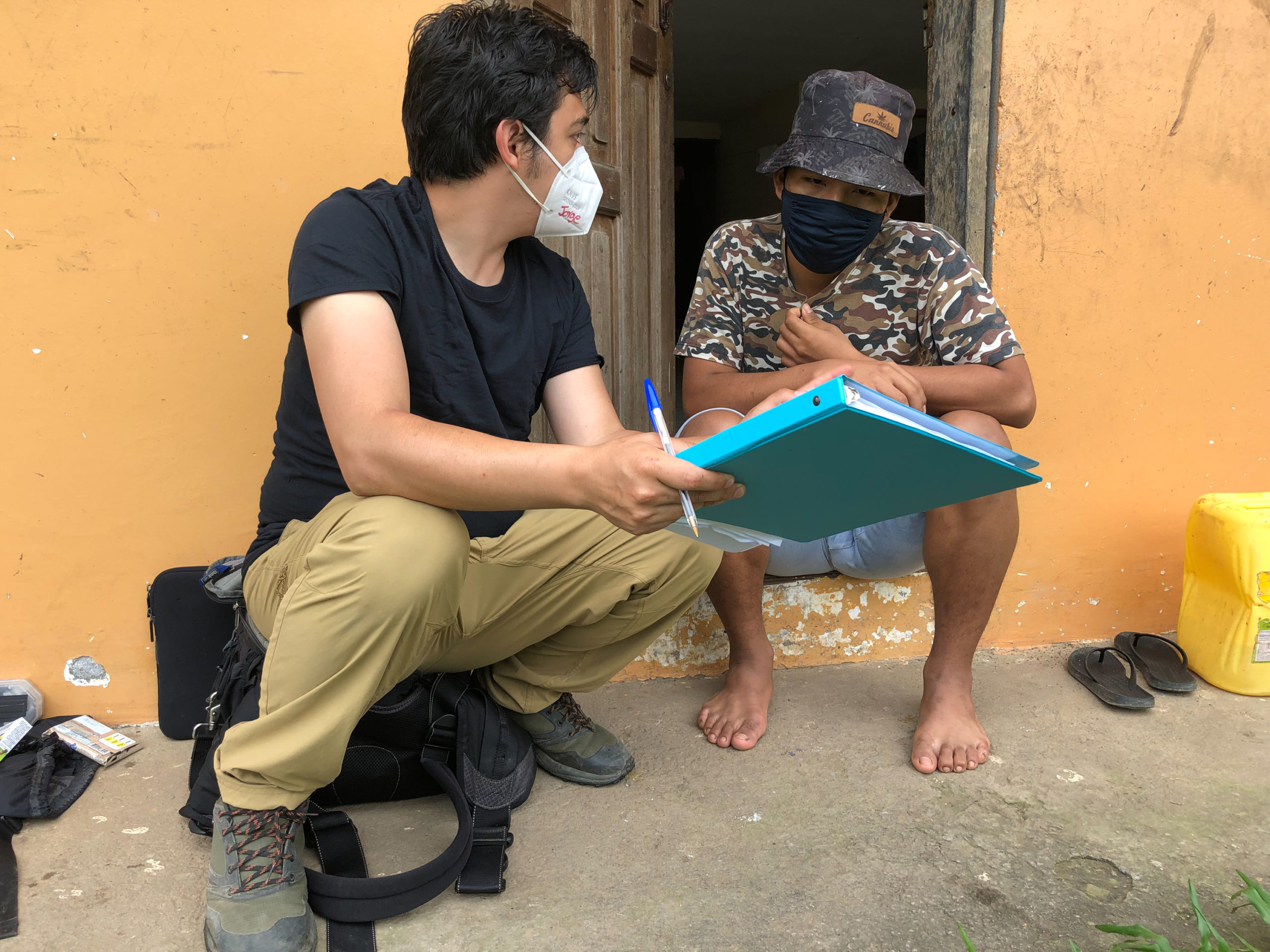

Jorge sits with a potential research participant during his selection interview at his home in the Dicaro.

Photo Credit: Diana Troya

Traditional Storytelling

To begin our participatory research, we started by offering a 6-day workshop focused on storytelling. What was most challenging about starting this workshop was the terminology. In English, we distinguish between story and history, so storytelling clearly refers to the general concept of sharing stories, not historical rhetoric. However, in Spanish, there is only one word used for both: historia. Oftentimes, it is the context of the situation that helps distinguish between the act of telling stories and the reiteration of a past experience.

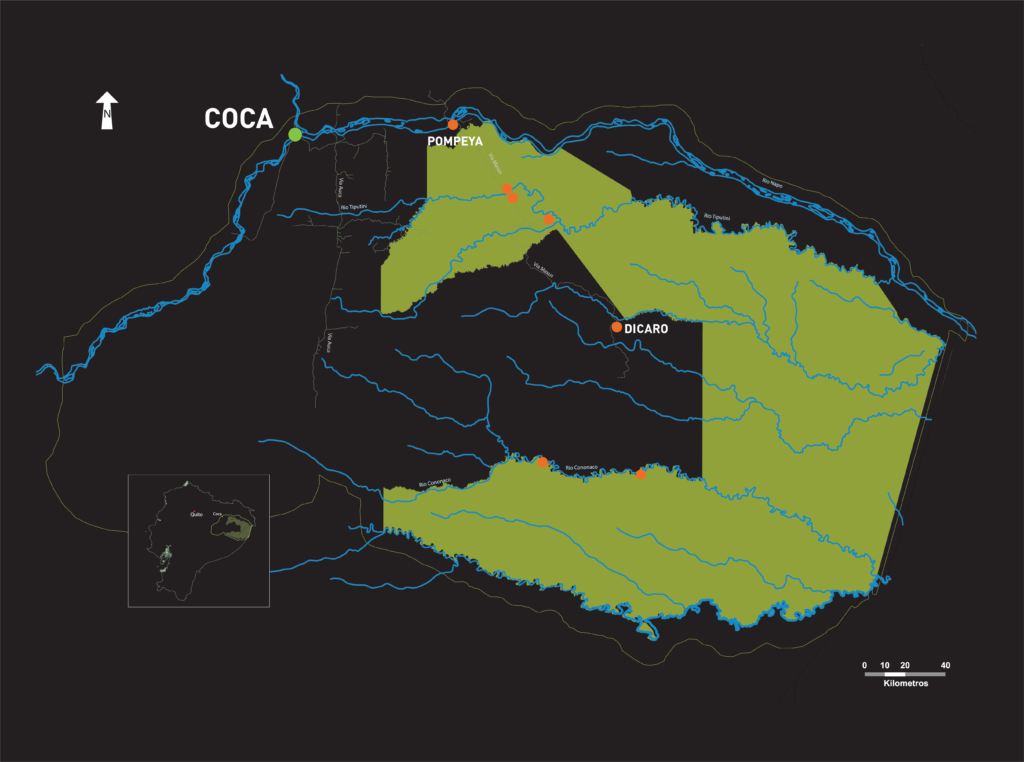

To facilitate in creating a common understanding of historia in terms of telling stories, Jorge and Diana offered several pre-designed activities to allow participants to share traditional cultural stories that had been passed down from one generation to the next. These included theatrical dramatizations, shared storytelling as a group, and hand-drawn/written stories.

Diana facilitates the shared storytelling activity during the participatory workshop after selection interviews were finished and participants finalized. Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

One of the research participants retells the story that he wrote and drew the night before as requested by the research team during the visual storytelling workshop in Dicaro. Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Immersive 360° Video Storytelling

Once our participants had warmed up their storytelling abilities (after all, Waorani communities have survived because of a rich traditional of oral storytelling), Jorge and Diana continued the workshop experience by sparking a conversation about the various tools that have been used throughout history to tell stories. This, in turn, led to our introduction of immersive 360° video storytelling as one of the most recent innovations in capturing and sharing stories.

After explaining that 360° video creates a sense of presence and immersion for the viewer on an entirely new level compared to traditional video, our participants donned head-mounted displays (HMDs) to watch 360° films that allowed them to virtually rock climb in Yosemite National Park, snorkel in Indonesia, and soar over their Amazonian territory. By experiencing these new sensations, each participant came to understand the potential power of immersive storytelling.

Research participants watch immersive films using head-mounted displays and cellphones.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Jorge explains to research participants how 360° cameras work and how to produce 360° films with them. Photo Credit: Diana Troya

To familiarize themselves with the production process for 360° films, research participants download the necessary software on their cellphones. Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Software Tools to Produce Immersive 360° Short Films

As we were preparing this research study, we knew from previous experience working in nearby communities that it would be most beneficial for participants to use their own devices to create media that captured their own stories. Without hesitation, Jorge Castillo Castro was able to devise a production method that involved the use of four cellphone apps so that participants could capture, edit, publish, and view 360° videos with their cellphones and HMDs.

Insta360 ONE X: Paired with an Insta360 One X camera, this app allows the user to operate the camera remotely, enabling them to view what the camera is capturing and avoid being part of the scene, if desired.

CapCut – Video Editor: This app allows users to trim and rearrange video clips and photos as desired to produce their final short films.

VRfix: Due to the unique qualities of 360 video metadata, it is necessary to use an app such as this that inject the metadata into the final film file so

Homido 360 VR Player: This app enables users to view 360 videos using their cell phones in a VR headset.

Independent Production: Self-driven Storytelling

In the two months that followed our intensive workshop facilitation, our participants were asked to continue exploring the process of 360° storytelling production on their own in and around the community. We left all the necessary equipment with them. They organized into three groups (as we had three 360° cameras and kits), some of which worked as a group and others switched off taking charge of the camera for their own individual productions.

During this period, participants worked together to solve technical problems. We wanted to understand how inter-community communication flowed when external agents of change like ourselves were not present to help remedy equipment problems or motivate action in general. Yet, we also wanted the participants to have enough collective knowledge and understanding gleaned from our month-long collaboration prior to this phase of the research project to assist one another if needed.

Equipped with a full 360° camera kit, a few of our participants experiment with shooting as they work on their own to produce immersive stories in Dicaro. Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Using specific apps on their cellphones, our participants were able to see live what the 360° cameras were filming since it is important to be far from camera to stay out of the frame. Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Once the film was captured, edited, injected with metadata, and shared to YouTube, our participants were able to view their productions using their cellphones in an HMD. Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro/Megan Westervelt

Virtual Communication between Hemispheres

As researchers, we felt it was crucial to stay in contact with our participants during this independent production period so that we could understand the ways in which immersive storytelling did or did not serve as a tool for the community to share their stories. Therefore, Jorge and Megan asked participants to meet with us once each week (or every other week, as they preferred). We met virtually using WhatsApp software on our smartphones, which is the most popular and common virtual communication tool used in Ecuador. For most meetings, we were able to both see and hear the participant, as they were also able to do with us.

During our virtual meetings, we would ask two simple questions: (1) how their immersive story production was progressing, and (2) if they had run into any technical obstacles that we could support them to overcome. While we did encourage participants to communicate with each other as questions or technical confusion arose, we also realized that this type of storytelling and technology was very new to everyone in the community, so our guidance could sometimes provide needed insight that none of the participants had yet.

Jorge and Megan meet with Karewa Tocari on WhatsApp to share in conversation about the immersive story he is working on about the cultural tradition of making chicha. Screenshot.

Concluding Interviews

At the end of the independent production phase of the research plan, Jorge and Megan returned to Dicaro to conduct final interviews with participants about their experience with the 360° storytelling production and with the research project overall. Several participants had gathered footage with the 360° cameras using, but problems with their smartphones had not allowed them to complete the process of editing, injecting with metadata, and sharing on YouTube. Therefore, we also provided a bit of technical support to get their stories online.

The concluding interviews focused on the three research questions of the overall study, respectively pertaining to traditional and digital storytelling in relation to natural resource use/biocultural conservation, as well as the role of the digital divide in producing such stories. Each participant shared their perspective about how they feel this new form of storytelling should be used in their community moving forward after the conclusion of the project.

Jorge listens as Jose Omehuai explains what he and his bother captured for their most recent 360° storytelling production about preparing fish for a family dinner at home.

Photo Credit: Megan Westervelt

Jose Omehuai, a participant in the research study, responds to Megan’s questions during the concluding interview for the project.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Exhibition for All: At-home and Community Presentations

As the end of our research study, we asked the participants how they wanted to share their immersive films with their community. Several of them demonstrated a desire to show their families at home using the HMDs. Others wanted to organize an inclusive showing for everyone in the sports complex at the heart of Dicaro. To show our appreciation to our participants, we as researchers also wanted to host a showing for participants and their families (during which we could then provide dinner).

In total, there were several private, at-home showings using the HMDs and three main community events, including a smaller one for participants and their families. The first showing actually occurred before the independent production phrase, the second after concluding interviews, and the final during our last trip to Dicaro two months later to bring the study to a close. Each exhibition grew in audience and excitement, and each allowed the participants to talk about their work with those who they live and interact with every day. Other community members who had not participated in the study itself shared their thoughts about this storytelling tool and collaborative effort after we showed the films. We also offered everyone the opportunity to use an HMD to view the films individually after we had seen them as a group using a computer and laptop (clicking and dragging around the screen).

Awa Nampahue fits an HMD on his wife in front of their home so that she can watch the 360° short film that he recently produced about his venture into the jungle to visit his family’s farm.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Awa Nampahue and his children react as they watch Awa’s wife experience his 360° short film that he recently produced.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro

Jorge welcomes the audience to a community public exhibition of the 360° short films that our participants produced during the previous month.

Photo Credit: Diana Troya

Children and adults gather to watch the short films produced by our participants at another public community exhibition.

Photo Credit: Jorge Castillo Castro